Massachusetts to Myanmar

Defying Expectations in Education

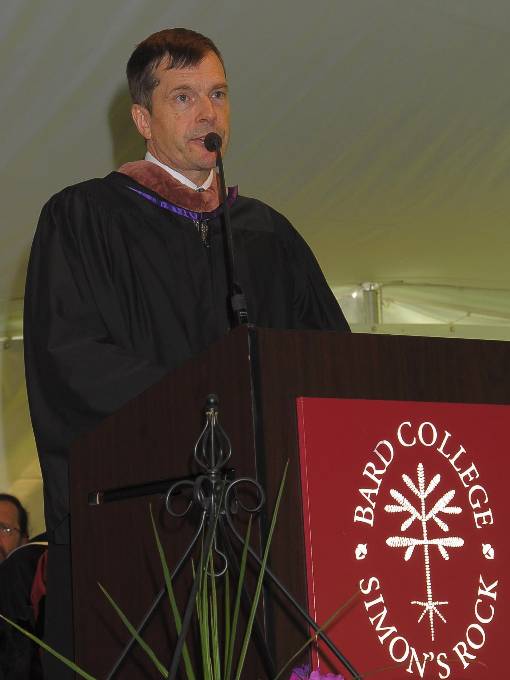

Parami Institute, founded by Kyaw Moe Tun ’05, is the newest in a long line of Bard College-affiliated campuses and partnerships created to serve student populations in some of the most difficult areas in the world.

by Ella Geismar ’13

“To discuss everything about our country, and what we gain and lose because of the development process, will take uncountable time, so let me stop my writing here. We must ask what we should do to prepare not only physically, but also morally, in order to ensure sustainable development for our country. How?”

These are the concluding lines of a Polished Piece of Prose that I recently read. Often abbreviated as “PPP,” the Polished Piece of Prose is a familiar exercise for Simon’s Rock students and alumni. Signifying the end of the intensive Writing & Thinking Workshop that marks the beginning of every student’s time at the college, and more recently, at Bard Academy, the PPP is meant to synthesize and celebrate the notebooks’ worth of writing produced throughout the workshop, to then be shared with fellow students and teachers.

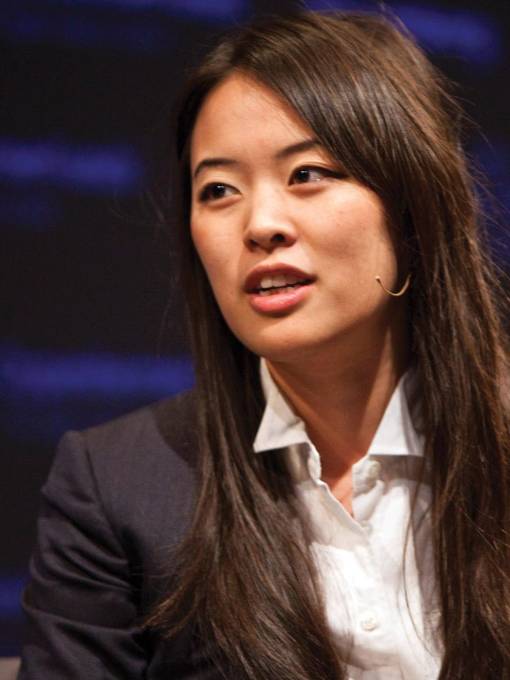

The above piece, which was written by a young woman named Stella Htetel, was created under similar circumstances. And, in fact, reading these few lines, it would be easy to imagine them being penned by any incoming first-year student at Simon’s Rock, or any of Bard College’s other campuses. For the author, however, the implications of these questions feel especially close at hand. Stella, who is from one of Myanmar’s minority ethnic regions, Kayah State, has personally witnessed the impacts of the development process in question. In the pages of her writing, Stella lays out firsthand experiences with the deforestation of massive teak forests, the creation of three hydroelectric power plants in her hometown, and agricultural decline due to climate change and the introduction of monoculture. As is often the case in Writing & Thinking, Stella’s essay blurs the lines between the political and the personal, embracing the complexities of that relationship with confidence.

Stella grew up in a convent, where rules were strict and opportunities limited. However, after high school, she had the chance to move to Yangon (formerly Rangoon), where she studied under a teacher who encouraged her to pursue new modes of thinking and self-expression. After a year in Yangon, she opted to continue her education and enrolled in a distance university, a popular model of schooling in Myanmar that only requires students to be on campus for final exams. Given the flexibility of the model, she knew that she could continue to pursue more meaningful, non-traditional educational opportunities in her own time. So, she enrolled in the Parami Leadership Program (PLP), a small but increasingly influential program located in Yangon. Geared toward recent university graduates (most of the students are between the ages of 20 and 26), PLP is an intensive, year-long academic program in the liberal arts and sciences.

Stella Htetel at Parami Institute

Now in her second month at PLP, Stella reports that her greatest challenge has been breaking out of her comfort zone and pushing herself to think in new ways. But her goals are coming into focus: in light of her own educational trajectory, Stella hopes to create an educational center for disadvantaged students in her hometown, sharing the styles of learning she’s learned at PLP.

Creating Opportunity

Dr. Kyaw Moe Tun ‘05 (known as Freddy while a Simon’s Rock student) founded Parami Institute in 2017. Parami is the newest in a long line of Bard College-affiliated campuses and partnerships created to serve students like Stella in some of the most difficult areas in the world.

“I feel compelled to create and share similar education opportunities that I once received at Simon’s Rock,” says Kyaw Moe Tun. “This education is highly needed to empower the Myanmar youth in critical thinking, interdisciplinary analysis, and articulate communication, to become future leaders of this country.”

Focusing on providing and improving higher education opportunities across the country through both programming and policy advocacy, Parami is working unabashedly to bring the liberal arts — with all of its rigor, complexity, and challenge to norms and conventions—to a country with a long history of oppressive rule and poor educational opportunities.

In PLP, which serves the core educational initiative of Parami Institute, students from across Myanmar’s vast ethno-linguistic spectrum study under internationally educated faculty, taking courses in the arts, humanities, natural sciences, and social sciences. Classes are student-driven, emphasizing collective learning through discussion of ideas, texts, and opinions. In fact, the classroom would be immediately recognizable to any Simon’s Rocker — a small group of students, seated in a circle, sharing ideas with enthusiasm. Parami structures its curriculum to broaden exploration through engaging discussions and uncompromising freedom of thought. And, as is the case at every Bard College campus across the world, the foundations for this way of being in the classroom are established in the Writing and Thinking workshop.

Students pose in front of Yangon’s Sule Pagoda

Students purchasing snacks from a street vendor

Writing & Thinking

At the start of this year, Parami Institute welcomed Simon’s Rock professor Dr. Chris Coggins as our Writing & Thinking Workshop leader. An expert in Chinese geo-political studies, Chris has been teaching, traveling, and studying in the East and Southeast Asian region for years, but had never been to Myanmar before he joined us in January. But as an experienced and adept workshop leader, Chris recognized something that lies at the heart of the workshop: wherever in the world it may take place, Writing & Thinking has the potential to shake the foundations of expectations and precedents in dramatic ways, shifting thinking and reframing understanding for students and teachers alike.

“At first it seemed easy because there are no rules. But . . . because there are no rules, it’s very difficult. There’s so much to think. There’s no limit, no boundary. — Nan Sanda Kue”

Over the course of two weeks, Chris guided students through texts and exercises that spanned Writing & Thinking standbys—including Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” and T. S. Eliot’s “Preludes”—to Myanmar-specific ones, including poems in Burmese and a writing exercise about locally foraged plants and leaves. For their final “PPPs,” students were asked to write “auto-ethnographies,” personal essays that shared personal and cultural anecdotes through descriptions of land and space. Over half of the students in the current cohort are from ethnic minority groups, and they represent every major region in Myanmar. Sharing these stories was an exercise in recognizing both shared commonalities — like the widespread economic growth and globalization that has reached nearly every corner of the country—as well as major differences in language, culture, climate, and beyond.

Though transformative for students anywhere, the invitation to openness and freedom of thought is distinctly radical here at Parami. Decades of military rule have left even younger generations hesitant to speak out, fearful of censorship or worse. Myanmar’s education system—a product of an oppressive military regime—continues to promote a culture of silence and conformity. From a very young age, students are punished for asking questions and rewarded for memorization and repetition above all else. The curiosity and vulnerability of ideas that Writing & Thinking necessitates is such a departure from the norm of Myanmar’s public school system that it can often be overwhelming for our students when they first arrive. The week after Writing & Thinking ended, I was sitting in a tea shop with Stella and a few other students. I asked what they thought of the experience. A young woman named Nan Sanda Kue immediately responded enthusiastically: “At first it seemed easy because there are no rules. But actually, because there are no rules, it’s very difficult. There’s so much to think. There’s no limit, no boundary.”

And thinking—thinking without limits, without boundaries—is more crucial here than ever before. In the wake of rapid and recent democratization after decades of isolation and military rule, the country is teetering on a familiar ledge—on one side, a dangerous backslide into xenophobia and dictatorship; on the other, meaningful economic development and a growing democratic process that represents all of Myanmar’s citizens. Empowering students to vocalize their thoughts has always been the stated goal of Writing & Thinking, but in a country scarred by violent silencing, the stakes are significantly higher and the impact significantly greater.

“I knew that this was a critical moment in the country’s history,” Chris wrote to me in an email after returning to Great Barrington. “I was eager to learn what smart, young students who hailed from many parts of the country … would have to say about their lives, the state of their nation, and their own goals and aspirations in the face of daunting collective and individual hardship. What better way to do this than through writing and thinking exercises that simultaneously challenge, engage, and, often, captivate both the teacher and the students, as all become more self-aware, more aware of the lives and hopes of others, and, arguably, more committed to the pursuit of communication by any means possible to amplify the communicative capacities of our collective communities?”

This need for cross-cultural understanding is central to Parami’s mission. Violent conflicts in Rakhine State have underscored deep-seated insecurities in Myanmar’s efforts toward legitimate democratization and peace-building processes that are necessary for long-term sustainability. Indeed, the plight of the Rohingya is part of a long history of violent military campaigns against Myanmar’s many minority ethnic and religious groups. Oppression of minority groups in Myanmar, often violent, is in no small measure the product of isolation, which in turn fuels prejudice and closed-mindedness. In this context, the classroom is one of the few spaces equipped to lay the necessary foundations for positive change, and the work happening at Parami, to students and faculty alike, feels pressing, not in spite of, but because of, the conflicts happening here.

The Founding And Future Of Parami

Officially opened in 2017, Parami Institute’s history and ties with Simon’s Rock began in 2011, when U Ba Win, former dean of students and provost at Simon’s Rock, and later Bard College’s Vice President for Early Colleges, was leading an initiative to open a four-year, residential liberal arts college near Mandalay, Myanmar’s other, more northerly metropolis. Ba Win had recruited Ian Bickford, then faculty in literature at Bard High School Early College Queens, to serve as the new institution’s academic dean, and together they approached Kyaw Moe Tun, who was finishing his PhD in chemistry at Yale, to serve as a founding member of the faculty. As an alumnus of Simon’s Rock who was born and raised in Yangon, Kyaw Moe Tun was a clear choice.

He was the first and also, it turned out, the last prospective faculty member to be offered a job at Bard’s notional Myanmar campus. Despite the momentum behind the school, key influencers in Myanmar retracted their support unceremoniously, effectively ending the project. They felt the country wasn’t ready for the kinds of open discourse produced in liberal arts classrooms. Kyaw Moe Tun disagreed, and he remained in Myanmar to continue the work, driven by the importance of the mission and his own ability to give back. “The major challenges were twofold,” says Kyaw Moe Tun. “One was convincing the Myanmar people to pursue liberal arts and sciences education. The second was development and fundraising.” He looked to his community to meet these challenges, and launching the school was a collaborative effort. Friends and connections from Myanmar-based organizations helped secure the space, design the classrooms, and publicize the program.

“It was not a given that he would come back,” says Ba Win. “It’s important to remember that things were really bleak when Freddy [was here] … There was no end in sight ... Certainly, very few Burmese students in that era returned. Because what would they return to? A military government that was, at the very least, suspicious of them, and not at all inclined to give them any position of authority.” Kyaw Moe Tun had been on a research team at Yale that was making important medical breakthroughs, and he knew he had a clear path to a major research position at a prominent lab. He also knew that returning to Myanmar was something he wanted to do, but wasn’t sure in what form. “But then in 2011,” he recalled, “U Ba Win sent me an email asking me to come back to teach in Myanmar. That really set off my decision to come back. None of this would really have been inspired without Ba Win.”

Kyaw Moe Tun’s ultimate goal is to create the residential, four-year school that Ba Win envisioned, accredited as a satellite campus of Bard College. President Leon Botstein has given his approval to the idea, noting that “Bard is proud to expand [the partnership] even further with the establishment of Parami University, an initiative that will offer a Bard-styled education to Myanmar’s young people.” For now, though, the PLP has served as an excellent and, despite its small size, high-impact educational program in Myanmar. In its current form, the PLP may only be a one-year program. But the enthusiasm and curiosity that pervade the Parami campus are no less present or intense than the same energies at Simon’s Rock, in the classrooms, the library, the studios, the laboratories, or the Interpretive Trail.

In this way, Parami has come to embody the ethos—I will call it the heart and soul—of the Simon’s Rock education that Kyaw Moe Tun and I both received, but in a wholly new and exciting context. Just last week, students petitioned to create a new weekly time slot for “knowledge sharing,” a time for one student to share expertise on something beyond the classroom with fellow classmates; the first speaker, who just graduated from a technological university, discussed data privacy. Named as an ode to the conversational atmosphere of Burmese tea shops, these “Tea Talks” embody an unadulterated enthusiasm for learning that only feels comparable to the attitude that defines the Simon’s Rock community.

At first, I had imagined these similarities to be due to the broad strengths of the liberal arts. But that only seems to be part of the equation. There are hundreds of liberal arts programs in the world, many teaching in the same way that our own schools do. But at Parami, as at Simon’s Rock, there is an additional, radical quality to the education our students receive: whether it comes from starting at a younger age or transcending political contexts, these learners are defying expectations and transgressing norms in order to access life-changing educational opportunities. In both places, nothing is taken for granted, and every moment in the classroom is recognized as important.

“As a geographer in a liberal arts institution,” Chris wrote at the end of his note to me, “I was struck by the effectiveness of combining liberal arts pedagogy with the worldly concerns that seem to burden our discipline to the breaking point … [but] working with the students in Parami helped me realize that the right kinds of changes begin with thoughtful conversations. These conversations are best preceded by a little writing and thinking. I emerged with a deep sense that these students will change the world for the better.”

Ella Geismar is an alumna of both Simon’s Rock and Bard High School Early College Queens. She currently serves as the Programs Director at Parami Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences. This article originally appeared in the Spring ’19 Magazine. Photos by Htet Oo Wai Yan.