Simon's Rock at 50

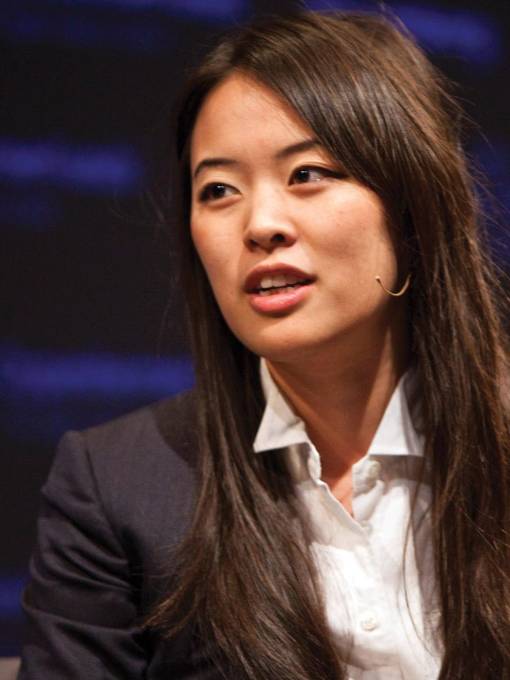

Veronica Chambers '87

Writer and Editor

It is still, nearly thirty years later, one of my most powerful memories. I am sitting in the office of Brian Hopewell, then dean of admissions at Simon’s Rock College, and I am hoping, praying, that he will let me in.

I am 16 years old. My grades are not bad, B+/A- range in nearly everything. But I am not a genius. I know this because when my high school assistant principal found out that I hoped to go to college early, he yanked me out of my homeroom and dragged me around the hallways of our school, ranting and raving about my ignorance. “This school is full of students who are smarter than you, more gifted than you, more ready for college in every single way possible,” he said. “Who do you think you are?” he growled again and again. Who do you think you are? “You will fail,” he warned. “Then you will be both a high school dropout and a college dropout. Good luck with that.”

I did not know who I was. But I was intimately acquainted with my circumstances. I had bounced from home to home, school to school, and state to state all my life. By the 11th grade, I had attended nearly 10 schools from Brooklyn to South Central Los Angeles. My current guardians were abusive. I had scar marks from where they had beaten me, some of them now thirty years old. I had slept on the street more times than I cared to remember. Sleeping on the streets being a euphemism. I was a teenage girl and I worried what might happen to me if I slept so what I did when I crept out of the house at night was walk, up and down the highway, through suburban cul-de-sacs and empty strip malls until the first light of day signaled the all clear for me to come home.

I was not a genius, but I liked to read. My family was from Panama, but I had been obsessed with African American history for as long as I can remember. I knew from the stories I read that my situation was challenging. It was not insurmountable. The tales of Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Frederick Douglass encouraged me to look for the “drinking gourd,” which is what slaves called the Big Dipper. The drinking gourd would lead me to the North Star that would lead me to a better place. Then one day, a brochure came in the mail, “Why Wait to Go to College?”

Veronica Chambers reading from the 2017 Book One

I took it to my guidance counselor, who was also my confidante, and she and I began to plan and plot. I applied to several colleges, but Simon’s Rock always stood out for me: a chance to go to college, and be with people my own age. I had done a lot of growing up in my sixteen years, but I found comfort in the idea that this was a school that would accept me at my age and challenge me intellectually but also be mindful of my emotional development. It meant a lot to me, as a black Latina, that the school was situated in the birthplace of W.E.B. Du Bois. I had not yet read the Souls of Black Folk, but I knew about Du Bois and his notion of the Talented Tenth. My heart quickened at the thought of somehow being able to tap into his tenacity, ambition, intellectual curiosity, and cosmopolitan elegance. His connection to the home of Simon’s Rock seemed like another sign that this would be the right place for me. Look for the drinking gourd.

I remember the day Brian Hopewell called to tell me that I’d been accepted at Simon’s Rock and that even more amazing, the school would give me a grant in the form of a W.E.B. Du Bois scholarship. I remember how infuriated the assistant principal was at this news and how bewildered I was that a man who’d never seemed to take notice of me before had decided to act as a one-man road crew, throwing up obstacle after obstacle to my achieving my dreams. Thank God for my high school counselor, Edna Chatmon, and how her joy at my acceptance counterbalanced all that I had to face with the administration and my family at home. Thank God for all those black history books, torn and tattered volumes that had been written in the 1950s and 1960s as part of a blueprint of hope for future generations. Because of that one black woman, because of those books, I knew that I would not fail. As I reminded myself often in my four years at Simon’s Rock, if Henry Box Brown could mail himself to freedom, I could do this.

“I was confident that the circumstances of my previous life made me a square peg trying to fit into a round hole. What I learned pretty quickly at Simon’s Rock was that square pegs were, in fact, the Simon’s Rock mold. Everybody was different, and individuality was prized.”

— Veronica Chambers

Like almost every freshman, everywhere, I thought that I was different from my peers. I was confident that the circumstances of my previous life made me a square peg trying to fit into a round hole. What I learned pretty quickly at Simon’s Rock was that square pegs were, in fact, the Simon’s Rock mold. Everybody was different, and individuality was prized. I did not come to Simon’s Rock to be a writer, but from the very first day of the Writing and Thinking Workshop, I realized that writing was going to be core to the experience of my education. I had immersed myself in the literature of women of color. This was the late 1980s and early 1990s, and there was an ocean of spectacular literature available by women like Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, Isabel Allende and Maxine Hong Kingston, and Louise Erdrich and Gita Mehta. But I learned in the classrooms of professors like Pat Sharpe, Arthur Hillman, Wendy Shifrin, Hal Holladay, Jamie Hutchinson, Peter Filkins, and Peter Cocks that writing was not to be tied to precious and grandiose notions of literature. Writing was a tool, a means of exploration, a way — to quote Adrienne Rich — “to explore the wreck. The words are purposes. The words are maps. I came to see the damage that was done and the treasures that prevail.”

It was this, the insistence of all that writing — not just paper after paper, but the dreaded response journals, presentations, and the like — that became the treasure of my education. I studied Picasso with Joan DelPlato and it is rumored that Picasso’s Bull is how Apple trains its employees to think more like Steve Jobs. In the 1945 lithograph, we see how Picasso strips down the realistic rendering into a series of lines and shapes that evoke something more powerful, more imaginative, something greater than the original whole. This is, I believe, the very crux of the Simon’s Rock education. Simon’s Rock at 50 is, now more than ever, more than a liberal arts lesson rooted in a tradition of critical thinking. Simon’s Rock is an innovation lab. It’s a school where your brain learns to think in 3-D. It is an education that can be applied to anything and everything.

I know this to be true because in the 25 years since I graduated from Simon’s Rock, I have been the youngest editor to be hired at the New York Times Magazine, a correspondent for BBC radio, an arts reporter for Newsweek magazine, a reporter in Japan, a four-time New York Times best-selling author, a children’s clothing designer, a director of brand development, a teacher, and a member of several nonprofit boards. I have built apps, written grants, and launched magazines. I’ve worked with art directors and architectural firms. I’m mostly called in to be the big-idea person, but I also know how to go micro. People count on me as a person who can get the job done. What job? Well, practically any job.

I’ve given more money to Simon’s Rock than any other organization (not a ton of money but a significant portion of what I’ve made) because I believe that our model of education is more vital than ever. I write this from Palo Alto where I’m spending a year as a fellow at Stanford, brainstorming about the future of journalism. I know that every room I will walk into this year, I’ll be bringing the lessons of the mentors who taught me — the professors I’ve mentioned and two critical forces of nature who taught me how to lead: Bernie Rodgers and Emily Fisher.

Thirty years ago, I thought that as a student of color, from a large urban area, with limited means, I was lucky to get into Simon’s Rock. I am so impressed with the Bard High School Early Colleges and the Bard Network and how thousands of kids in the types of schools that I grew up attending have access to the same incredible education that I received at Simon’s Rock. There is a true north to the education of Simon’s Rock. It has been, since the very beginning, about innovation, vision, bold moves, risk taking and blue-sky thinking. It started with Elizabeth Blodgett Hall, continued with Leon Botstein, and this is the thing: at 50, it’s just getting started.

“…You leave with a sense of your own true north that can guide you anywhere and everywhere.”

— Veronica Chambers

My friend Lorene Cary told me that it was on a cold and clear night, walking across the Simon’s Rock campus, that she was able to envision the scenes that would lead to her award-winning novel, The Price of a Child. Simon’s Rock is a small place from which you can see a thousand stars. In the best of circumstances, when those stars align, when the staff and professors offer up their gifts and you are able to receive them, you leave with a sense of your own true north that can guide you anywhere and everywhere. It is the college’s 50th birthday, but the gift lives in us.

Veronica Chambers is a prolific author, best known for her critically acclaimed memoir, Mama’s Girl. In 2017, Veronica will publish two books: The Meaning of Michelle: 15 Writers on Our Iconic First Lady and How Her Journey Inspires Our Own and The Go-Between, a young adult novel.