Seeing the Forest Through the Trees

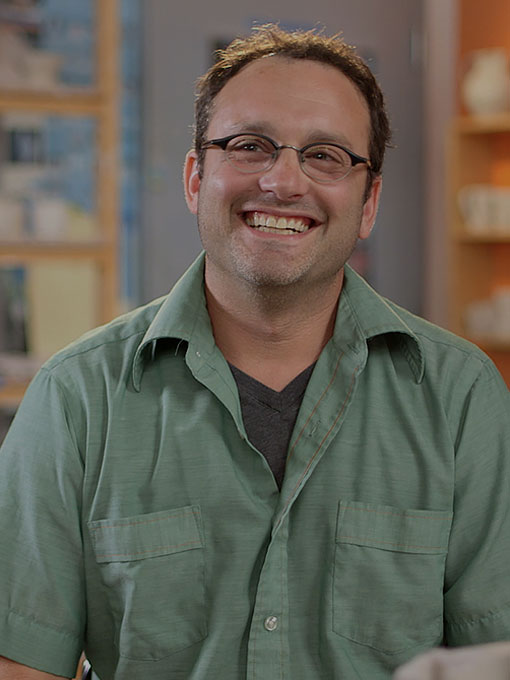

Dr. Chris Coggins

Professor of Geography and Asian Studies

For centuries, southern Chinese villages used the concept of feng shui to manage the forests to protect settlements and provide the ideal location for water conservation and crop cultivation. The word “feng shui,” more often associated with a type of divination, actually just translates simply to “wind” (feng) and “water” (shui). But where are the fengshuilin? And what can we learn from them?

When Dr. Chris Coggins, professor of geography and Asian studies, first learned of the feng shui forests of China’s rural mountain villages, he was taken aback. Chris was conducting research on the history of human-wildlife interactions and contemporary conservation efforts in Fujian province when a Chinese colleague pointed to a broadleaf forest on a mountain next to a small village, and said (in mandarin), “That’s a feng shui forest; you may want to learn more about those.” Before long, Chris’s field research project included systematic surveys of the sociocultural and ecological significance of these sacred groves that appear only intermittently in Chinese and Western records.

“In the literature there were a number of references to village ‘burial forests,’ earth god shrines, and lineage temples, all of which suggest a deep concern and long-term engagement with both ecological and cosmological principles of landscape design and management,” Chris said. “But the geographic extent, cultural history, and ecological value of these forests (fengshuilin) have not been systematically surveyed. We don’t even know where all of the forests are.”

He worries about taking students into certain areas to conduct research and then discovering that there aren’t any feng shui forests there.

But he and his students have found them, and now Chris Coggins, along with Bard, Bard High School Early College (BHSEC), and other Simon’s Rock faculty and students, have been given the chance of a lifetime by the Henry Luce Foundation that awarded Bard College a four-year $400,000 Luce Initiative on Asian studies and the environment grant to increase and enhance the interdisciplinary study of environmental and sustainability issues in Asia.

Aris Efting, BHSEC Queens professor of biology, Chris Coggins, and Alex Danza ’11 test water quality in a stream in a Fujian feng shui forest

The grant will fund Bard’s environment and Community in East Asia Initiative to develop new courses and enhance existing ones with a focus on the environment in Asia. The initiative will also expand research opportunities for undergraduate students to study environmental issues in China, Japan, and Korea.

Chris, along with a team of three Simon’s Rock and Bard students, and other colleagues—including an aquatic ecologist, a dendrochronologist, and a cultural studies expert—just finished their first (of three) summer research treks to Fujian and Jiangxi provinces to study the area around Lake Poyang, China’s largest freshwater lake. What they found was exactly what they had hoped for, and much more, thanks mostly to the diversity and tenacity of the team—a ceramics major, an Asian studies major, and a potential environmental science major—many of whom had never conducted rigorous fieldwork before.

“We would get to a village, always with a liaison, either with the Forestry Bureau or some other local authority—as a foreigner, don’t just show up in villages in China. And then we would break up into teams and spend countless hours doing research.”

Chris continued, "We learned a lot and got a tremendous amount done. I would be interviewing older villagers, sort of getting the taxonomy of feng shui forests and how they fit into the scheme of village life. Others would be testing/taking water samples or getting ancestral records or bushwhacking through tropical forest to find streams. We also had three students doing documentary filmwork.”

Jade Mermini ’11 seems to have been taken in by the magic that the ancients referenced when writing about the fengshuilin. Jade, who was born in Fujian but later adopted and taken to the United States, studies Asian studies and religion, was drawn toward the storytelling element of the adventure and the surrounding lands of Lake Poyang. In addition to centuries-old untouched forests, Jade found something else as well.

“Visiting and connecting in Fujian and Jiangxi gave me the chance to experience elements of myself I had never been in touch with. I sucked in the elements of change that clung heavy to the air. The opportunities that came out of this journey were the most intimate of blessings and freedom that a Chinese-born girl in my shoes could have dreamt of.”

Jade Mermini '11, Meihuashan Nature Reserve, Fujian

Engaging students like Jade as well as faculty in a three-year multidisciplinary project will not only provide them with an opportunity to study the many facets—human, ecological, aquatic, political—of feng shui forests but will also shed light on the potential that the forests provide as seed banks for reforestation and as biologically diverse areas.

“These forests are very important to people in China and to the government where, contrary to our popular cultural belief, there is a huge push toward nature conservation,” Chris says. “And there is a lot that we in North America can learn from these forests, especially about water quality, agriculture, and fundamental relationships between people, places, and nature. Now that the team and I have made the first trek, we know where we need to go and what we need to do once we get there.”

Meet Our Community

Maryann Tebben

Professor of Language and Literature - French